Epstein's Really Big Short: How US Taxpayers (And Big Bankers) Bailed Him Out

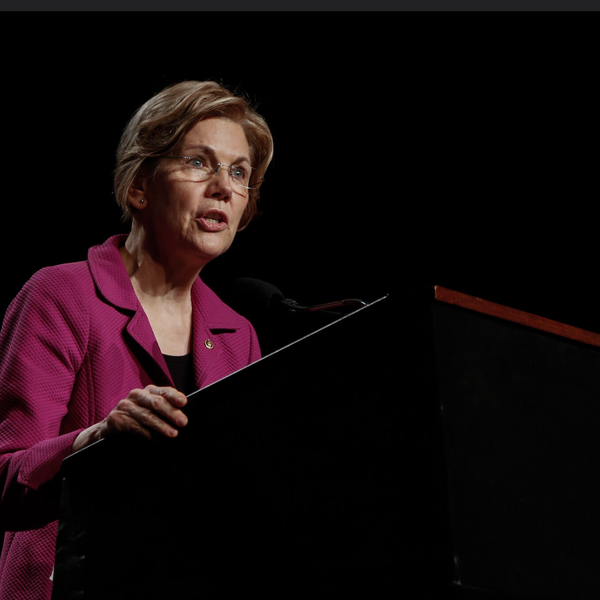

Margot Robbie in "The Big Short"

If you paid federal income taxes back during the 2008 fiscal crisis, you may not know it, but the sad truth is that it you were likely bailing out Jeffrey Epstein as well—to the tune of nearly $7 billion.

It’s a story that has remained hidden from the public even as the Department of Justice has released hundreds of thousands of documents (and has withheld far, far more) that shine a light on how Epstein orchestrated one of the most salacious scandals in American history.

Put simply, the evidence overwhelmingly suggests that, thanks to the Wall Street Bailout of 2008, American taxpayers paid off the liabilities of an obscure offshore company called Liquid Funding Ltd. that was chaired by Jeffrey Epstein.

The total amount of the bailout was $6.7 billion and the liabilities were incurred because Liquid Funding had issued the same kind of arcane financial securities that created the worst economic catastrophe since the Great Depression. In other words, the 2008 financial crisis not only stripped millions of Americans of their jobs, their homes, and their financial security, but it also led to American taxpayers paying for liabilities sustained by the principal figure in a conspiracy that involved sex trafficking, sexual abuse, extortion, money laundering, tax evasion, securities fraud, and much, much more.

To be sure, we already know a lot about how Epstein assembled his empire: the alleged $475 million Ponzi scheme that left co-schemer Steven Hoffenberg holding the bag—and serving 18 years in prison; Leslie Wexner’s transfer of his massive Upper East Side mansion and sweeping power of attorney; Leon Black’s $170 million in payments for “tax advice.” All told, it added up to a $578 million estate when Epstein died in 2019.

Investment Fund Exposed In 'The Paradise Papers'

But Epstein was also chairman of an offshore Structured Investment Vehicle called Liquid Funding Ltd., from 2001 to 2007, a period at the height of the mortgage security boom during which he was regularly committing sex crimes. The information first came to light thanks to a database created by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ) containing files known as the "Paradise Papers" that were leaked in 2017 from the Appleby law firm.There was another fortune, hidden in the offshore world—one that would cost American taxpayers billions and has remained largely invisible for decades.

To understand what Epstein was doing at Liquid Funding, let’s go back to 2008, an era when the amped up, coke-fueled Big Swinging Dicks of Wall Street feasted on tranches of risky credit default swaps, residential mortgage-backed securities, collateralized debt obligations and all sorts of arcane securities that were sold to pension funds and conservative investors as “safe” when their chief attribute was that they were so insanely complex—and deliberately so— that no one understood what was inside them or the risks.

To refresh your memories, think of the movie version of Michael Lewis’ book, The Big Short, in which Margot Robbie sips champagne in a bubble bath as she delves into the arcana of toxic mortgage-backed securities.

“By the way,” Robbie says, “whenever you hear ‘subprime,’ think ‘shit.’

Add in the strippers who are living large with half a dozen properties financed by subprime mortgages, and the highly-leveraged, casino-like Wall Street culture that makes Vegas pale by comparison, and—well, you get the idea.

The story of Liquid Funding takes place in the private and secretive Land of Offshore Wealth, a gray zone hidden from all regulatory mechanisms, that, according to James Henry of the Tax Justice Network, may have more than $30 trillion hidden in tax havens— $40 trillion, if yachts, real estate, and artwork are included. That means an economy significantly bigger than the entire US economy is operating in jurisdictions most notable for their impenetrable secrecy: the Cayman Islands, the British Virgin Islands, Bermuda and Panama in the Western Hemisphere; Switzerland, Luxembourg, and the Channel Islands in Europe; Cyprus and Malta in the Mediterranean; and more in Asia and the Middle East.

It is a world populated by Russian oligarchs, European royalty, Arab sheiks, titans of Wall Street and Silicon Valley broligarchs with their super yachts and bespoke private jets, living in an almost cartoonish, James Bond-like world of greed.

And thanks to the complicity of banks such as JPMorgan Chase, Deutsche Bank, UBS, Credit Suisse, HSBC, and Citigroup, the offshore world provides the ultra-wealthy a means of moving assets through shell companies and nominee directors, creating layers of opacity that make beneficial ownership nearly impossible to trace.

For six years, while Epstein ran a sex trafficking operation, he simultaneously chaired a $6.7 billion offshore vehicle loaded with the same mortgage-backed securities that would trigger the worst economic crisis since the Great Depression.

All of which means it’s a parallel financial universe that hides the fortunes of a global elite from public scrutiny and tax authorities. Its most prominent beneficiaries include Vladimir Putin, with estimates of his hidden wealth going as high as $200 billion, and Donald Trump, whose use of Deutsche Bank remains obscured by the same secrecy mechanisms that protect other billionaires.

For Epstein, the road to Liquid Funding Ltd. began more than four decades ago, after his ignominious 1981 departure from Bear Stearns, where he had risen rapidly from a lowly floor trader to limited partner before leaving under circumstances involving regulatory violations that were never fully disclosed.

The 'Offshore Magic Circle' Of Financial Secrecy and Tax Evasion

In 1996, Epstein became a resident of the U.S. Virgin Islands. Two years later, he set up a financial consulting firm called Financial Trust Company—a move that allowed him to reduce his federal income taxes while still maintaining access to U.S. banking. Then, four years later, Epstein’s new company, Liquid Funding, became a client of Appleby, a top-of-the-line Bermuda-headquartered law firm that’s part of what the Financial Times calls the “Offshore Magic Circle.”

Within that world, Appleby, with offices in the Cayman Islands, the British Virgin Islands, the Isle of Man, the Channel Islands, and the Bahamas, was the law firm of choice for an elite clientele that included everyone from Queen Elizabeth to Russian oligarchs such as Roman Abramovich, Arkady and Boris Rotenberg, and Oleg Deripaska, others. Appleby was particularly well versed in helping wealthy clients whose assets include offshore companies in low-tax, high secrecy jurisdictions like Bermuda—which has no corporate tax rate whatsoever.

In 2016, however, Appleby was the subject of a data breach that resulted in over 13.4 million confidential electronic documents relating to offshore investments, including Liquid Funding, being leaked to the ICIJ. Those documents became known as the Paradise Papers.

In 2001, long before the Paradise Papers were released, Jeffrey Epstein became the chairman of Liquid Funding Ltd., a complex structured investment vehicle that was 40 percent owned by Bear Stearns, and managed out of Dublin, Ireland.

Although the remaining ownership has not been disclosed, it is likely that Epstein, as chairman, had a significant stake in the company. “It would be unprecedented for Epstein to be chairman and a director of a company in which he didn’t own a substantial amount of equity.” says James Henry, a Global Justice Fellow at Yale who has spent years investigating corruption in the world of offshore finance. (Niels Groeneveld, a Dutch security analyst who researched the Paradise Papers, reported that Epstein likely owned as much as 40 percent of Liquid Funding—the same stake held by Bear Stearns.)

Epstein’s ties to Bear and JPMorgan allowed him to work in this world of impenetrable opacity with no accountability whatsoever. “Epstein and Bear Stearns were both in the business of not being regulated,” says Henry. “Liquid Funding was a special purpose vehicle which had no majority owner, which meant it had no beneficial ownership requirements. It wasn’t subject to all the rules that the US was adopting on auditing such entities, and it was able to sell securities in the European market as well. So, basically it had no taxes. And because it was managed out of Bear Stearns in Dublin, it had even more regulatory advantages. They set it up in Ireland specifically to avoid any regulation.”

Issuing Billions In Equity With Almost No Collateral

One benefit of these regulatory loopholes was that Liquid Funding was allowed to issue billions of dollars of securities even though it had, relatively speaking, just a tiny amount of equity. Indeed, according to Wall Street on Parade, an independent financial news site run by Pam and Russ Martens, Liquid Funding had only had $100 million in equity, but the Fitch regulatory agency allowed it to issue up to $20 billion in securities—a ratio of 200 to one.

However, even that figure significantly understates how highly leveraged Epstein’s company was. Out of Liquid Funding’s $100 million in equity, only $37 million was drawn equity. The other $63 million was not actually invested in Liquid Funding, and that meant for every dollar that was put into his operation, Epstein was allowed to sell around $540 worth of securities.

So if his investments went up, Epstein would make a killing.

On the other hand, if they went south, it could spell disaster.

Now let’s look at exactly what securities Liquid Funding was selling to investors. This was a period during which the big ratings agencies—Fitch, Moody’s and Standard & Poor’s —routinely handed out AAA ratings to investments consisting of tranches of highly dubious asset backed securities and repackaged adjustable subprime mortgages.

If that sounds like a bunch of mumbo jumbo, that was precisely the point. During the fiscal crisis no one really understood all the insanely complex tranches of subprime mortgages. Worse, it had become standard procedure for the credit agencies to help dress up these unfathomably toxic assets with AAA ratings. All the agencies went along with it because if they didn’t, their competitors would.

But investors didn’t know that. Historically, the housing market always held. Homeowners always paid their mortgages. Conventional wisdom had it that nothing could be more secure than mortgage-backed securities. As a result, everyone stuck to the same script, and, thanks to the stellar ratings, investors gobbled up the securities.

In the mid-2000s, however, millions of low-income homeowners who had been enticed into the housing market by low introductory rates could no longer afford their homes once adjustable rates started going through the roof. When that happened, homeowners began to default. That meant that the securities based on those mortgages had been transformed into a time bomb that was about to explode and become utterly worthless.

That’s what subprime really meant.

*

Notwithstanding these overhyped securities, Epstein did have something else going for him. “The guy’s a genius,” Douglas Leese, an arms dealer friend of Epstein’s, told a colleague. “He’s great at selling securities. And he has no moral compass.”

On Wall Street, that last attribute was especially desirable in the early 2000’s. So, on October 19, 2000, Liquid Funding was launched. According to the Miami Herald, Marcus Klug, a director of Liquid Funding, said “there was neither a physical board meeting nor a call between board members.”

That meant Liquid Funding was a shell company—nothing more—with Epstein at the helm. It had the clout afforded by powerful financial institutions such as Bear Stearns or JPMorgan. But it existed in an offshore world populated by Russian oligarchs and money launderers, arms dealers and drug czars. Given its Bermuda-registration, its secretive shareholders, and its nominal governance, it had immense transactional latitude.

Backing Epstein's Shell Company, The World's Most Powerful Bank

Even though Liquid Funding existed in that “gray zone,” it was able to issue billions of dollars of securities because Epstein was wired in to some of the most powerful financial institutions in the world. JPMorgan was Liquid Funding’s “Security Trustee,” which meant that the bank held all of its securities and had the authority, if necessary, to liquidate all assets if Liquid Funding defaulted. Two Bear Stearns board members, Jeffrey Lipman and Paul Novelly, also served on Liquid Funding’s board. And another member of Liquid Funding’s board, Liam MacNamara, was on the board of JPMorgan Dublin.

Epstein also had considerable clout at JPMorgan because he had brought in billionaire clients such as Bill Gates, Leon Black (co-founder of Apollo Global Management), Glenn Dubin of Highbridge Capital Management, and Google co-founders Sergey Brin and Larry Page. (Brin later deposited $4 billion in assets at the bank.) Altogether, they made Epstein the highest revenue generator for the biggest bank in the richest country in the world. As such, he was a member of an elite group that was referred to as JPMorgan’s “Wall of Cash.”

At JPMorgan, Epstein had a champion: Jes Staley, the bank's Private Bank chief and later head of the investment bank, whom The New York Times would call Epstein's "chief defender." Despite mounting red flags—cash withdrawals, suspicious payments, a 2006 indictment for soliciting minors—Staley kept Epstein as a client until 2013.

Nevertheless, as reported in 2024 by Aly McDevitt in Compliance Week, an online publication that covers corporate governance, JPMorgan noted suspicious behavior in Epstein’s accounts even before his prosecution, and by 2003 the bank had begun regularly writing up Suspicious Activity Reports (SARs) and currency transaction reports for transactions that exceeded $10,000 in a 24-hour period.

But banks are required by law to file SARs to FinCEN (Financial Crimes Enforcement Network) within 30 days of suspicious transactions to assist law enforcement, and JPMorgan failed to do so. “There’s no chance that JPMorgan didn’t know that these SARs had to be filed within 30 days,” says James Henry. “They literally file millions of these things. But in this case, they were just sitting there.”

According to court filings by the Attorney General of the US Virgin Islands in a lawsuit against the bank, the reason JPMorgan continued to indulge Epstein was quite simple. “JPMorgan turned a blind eye to evidence of human trafficking over more than a decade because of Epstein’s own financial footprint and because of the deals and clients that Epstein brought and promised to bring to the bank,” the USVI lawsuit asserted.

More specifically, at the time, Epstein had cultivated extremely close ties to Staley, the CEO of JPMorgan Asset Management who was the presumptive heir apparent to JPMorgan Chase CEO Jamie Dimon. According to the USVI lawsuit, Staley and Epstein were so close that they exchanged approximately 1,200 emails between 2008 and 2012. In the emails, Staley, who visited Epstein’s Caribbean island multiple times, described their friendship as “profound.” Epstein responded to Staley that he was “family.”

By March 2005, the Palm Beach Police Department had started an investigation of Epstein, and in July 2006, police arrested him for procuring a minor for prostitution. The next day, Staley met with Epstein at his New York Office. Afterwards, Staley wrote a colleague at JPMC, “I’ve never seen him so shaken. He also adamantly denies the ages [sic].”

Staley visited Epstein while the latter was on work release in Florida in 2008, according to the U.K. Financial Conduct Authority’s case against Staley. He also visited Epstein’s ranch in New Mexico during that period, as he recounted in an email to Epstein that was cited in the USVI lawsuit:

“‘So when all hell breaks lose [sic], and the world is crumbling, I will come here, and be at peace. Presently, I’m in the hot tub with a glass of white wine. This is an amazing place. Truly amazing. Next time, we’re here together. I owe you much. And I deeply appreciate our friendship. I have few so profound.’”

Their friendship was so strong that seven years later, in 2015, Staley was moved to write Epstein about his deep bond with the pedophile. “The strength of a Greek army was that its core held shoulder to shoulder, and would not flee or break, no matter the threat,” Staley wrote. “That is us.”

A Jane Doe lawsuit brought against the bank eschews the warm and fuzzy nature of the friendship between the two men and instead characterizes it as a “symbiotic” relationship in which “Epstein agreed to bring many ultra-high wealth clients to JP Morgan, and in exchange, Staley would use his clout within JP Morgan to make Epstein untouchable. This meant that JP Morgan would keep Epstein on as a client at all costs, including failing to act on any red flags and ultimately allowing him the ability to run and grow what to the bank was obviously an operation designed to sexually abuse and traffic countless young women.”

Ultimately, the lawsuit claims that “Staley was the key to making all of Epstein’s depraved dreams of sexual abuse and sex trafficking of countless young women possible. With his help, the number of victims of the Epstein sex trafficking operation began to grow on a vertical trajectory beginning in 2000.”

The Chase Banker And Jeffrey's 'Girls'

According to Reuters, however, Staley “said he did not know Epstein would coerce young women and girls into having sex, or that anyone under 18 would be pressured into sex.” He also called the allegation that he sexually assaulted Jane Doe 1 “baseless.”

The relationship between the two men continued even after Epstein’s 2008 guilty plea to two state charges involving sex, one of which was with an underage girl. In March 2025 court testimony, Staley admitted he had sex with one of Epstein’s assistants, though he claimed he didn’t know about Epstein’s involvement with underage girls. Some of Staley’s emails to Epstein appeared to contain sexual references using apparent code words for young women. In one exchange, Staley wrote “That was fun. Say hi to Snow White.” Epstein replied: “What character would you like next?” To which, Staley responded: “Beauty and the Beast.”

Staley could not be reached for comment. However, in a letter to the Financial Times, Kathleen Harris, a lawyer at Arnold & Porter who is representing Staley, said, “We wish to make it expressly clear that our client had no involvement in any of the alleged crimes committed by Mr Epstein, and codewords were never used by Mr Staley in any communications with Mr Epstein, ever.”

Staley remained the manager of the bank’s relationship with Epstein until his tenure at the institution ended in 2013. Until then, whenever JPMorgan executives recommended cutting ties with Epstein, Staley went to bat for him, and, at times, went to him for advice.

Indeed, in October 2008, while Wall Street was being engulfed by the fiscal crisis, Staley reached out to Epstein for help and said he needed “a smart friend to help me think through this stuff. Can I get you out for a weekend to help me.”

Meanwhile, JPMorgan had delayed filings of its SARs concerning Epstein year after year. Indeed, it was not until shortly after Epstein’s death in 2019, that JPMorgan filed a massive Suspicious Activity Report (SAR) with the U.S. Treasury Department’s Financial Crimes Enforcement Network, flagging over 4,700 suspicious transactions in Epstein’s accounts involving more than $1 billion going back as far as October 2003. Some of the SARs were not filed until nearly seventeen years after the transaction had taken place.

In November, Sen. Ron Wyden (D-OR), the ranking member of the Senate Finance Committee, called for JPMorgan to be “fully investigated to determine whether this underreporting of Suspicious Activity Reports (SARs) was deliberate.” But Wyden’s bill to make public the SARs, the Produce Epstein Treasury Records Act (PETRA), failed to pass the Senate, thanks to Republican opposition. As Wyden’s colleague, Jeff Merkley (D-OR) put it, “51 Senators in this body, I am ashamed to say, said, ‘Hell, no. We want them kept secret. We want to protect the perpetrators.’ Why? Because the man in the Oval Office, Mr. Trump, told us he wants to protect those files, does not want them to go public.”

*

Meanwhile, notwithstanding his disgraceful departure from Bear Stearns in 1981, Epstein continued to maintain close friendships with its CEO Jimmy Cayne and its chairman, Alan “Ace” Greenberg. He also remained a client of the firm until its 2008 collapse, and his relationship with them appears to have figured prominently in the rise and fall of Liquid Funding.

But the camaraderie Epstein had with Cayne and Greenberg did not extend to the whole of Bear Stearns, which Epstein prepared to sue after the investment bank collapsed in March 2008. Bloomberg reported that the draft complaint further portrayed Epstein as an innocent victim who had been “fraudulently induced” by manipulative bankers to buy and hold stakes in funds that were riskier than advertised.

And indeed, as the housing bubble inflated toward its breaking point, the subprime market began collapsing. In June 2007, JPMorgan abandoned the market. Deutsche Bank held on, but barely. Goldman Sachs actually got out of the subprime market and bet against it. That, of course, accelerated its descent.

All of which left Bear Stearns—and, with it, Liquid Funding—in an increasingly untenable position. In June, after receiving margin calls, Bear Stearns attempted to bail out two of its hedge funds with $3.2 billion. But that wasn’t nearly enough. The funds held $17 billion in highly leveraged CDOs backed by subprime mortgages and, by July had lost nearly all their value, forcing them into bankruptcy.

As for Liquid Funding, according to Wall Street on Parade, Bear stated in a regulatory filing that “The Company’s maximum exposure to loss as a result of its investment in this entity is approximately $5.0 million.”

Five million! That was peanuts. By this time, Liquid Funding had liabilities in the billions.

At the same time all this was going on, Epstein continued to nurture his relationship with JPMorgan Chase by sending them more billionaires and cultivating his friendship with Jes Staley. Under Staley’s aegis at the bank, client assets expanded from $605 billion to nearly $1.3 trillion, as a result of which he was widely regarded as Dimon’s heir apparent.

Meanwhile, as Epstein’s sex trafficking empire continued to grow, the bank turned a blind eye to his activities. According to court documents in the Virgin Islands lawsuit, “Between 2003 and 2013, Epstein and/or his associates used Epstein’s accounts to make numerous payments to individual women and related companies. Among the recipients of these payments were numerous women with Eastern European surnames who were publicly and internally identified as Epstein recruiters and/or victims. For example, Epstein paid more than $600,000 to Jane Doe 1, a woman who—according to news reports contained in JP Morgan’s due diligence reports—Epstein purchased [as a sex slave] at the age of 14.”

In addition, according to The New York Times, huge cash withdrawals in 2004 and 2005 from Epstein’s personal account at Chase went to procure young girls and young women. At Epstein’s request, the bank even agreed to open accounts for two young women without ever speaking to them. According to an expert report filed in the Virgin Islands lawsuit, “it is well known that Epstein paid his victims in cash.” According to Wall Street on Parade, the report documented that Epstein withdrew $840,000 in cash in 2004. In 2005, he withdrew $904,337. In 2006, he withdrew $938,625. In 2007, he withdrew $526,000. When JPMC confronted Epstein about the cash withdrawals in 2007, Epstein claimed it was for “fuel payments in foreign countries,” which JPMC knew was “not normal business practice.”

Paying $31 Million To 'Girlfriend' Ghislaine

And finally, according to Compliance Week, there were reports that Epstein transferred approximately $31 million to Ghislaine Maxwell through his JPMorgan accounts between 1999 and 2007, funds that were “believed to be payment for her role in Epstein’s sex trafficking venture.”

In 2007, as the mortgage-backed securities bubble began to burst, Epstein resigned his chairmanship of Liquid Funding under circumstances that remain unclear. The timing coincided with federal prosecutor Marie Villafaña drafting a 53-page, 60-count indictment against Epstein—suggesting he may have been cleaning up his affairs in advance of plea negotiations.

Meanwhile, Liquid Funding, thanks to its proximity to Bear Stearns, was in trouble. On March 13, 2008, Bear Stearns delivered a startling ultimatum to the Federal Reserve: If it did not provide billions of dollars in funds within 24 hours, the firm would file for bankruptcy. And if that happened, its collapse could trigger a systemic failure across global financial markets.

Astoundingly, the very next day, on March 14—a Friday— the Fed invoked emergency lending authority for the first time in its history and provided a $12.9 billion emergency loan to keep Bear Stearns alive.

It did exactly that—but only through the weekend.

By this time, Timothy Geithner, the president of the Federal Reserve of New York, knew how desperately the government needed a reputable institution to take over Bear Stearns and quell the panic. Over that March weekend, he negotiated with JPMC CEO Jamie Dimon, who held a much stronger hand. “Jamie Dimon basically dictated terms to the Federal Reserve,” says financial investigator James Henry, who has studied the bailout extensively. “He said, ‘If you want Morgan involved in this deal, you’re going to have to do the following’ And they bent over backwards to accommodate JPMorgan.”

To that end, Geithner and Dimon signed an agreement by which the Federal Reserve created a special purpose vehicle called Maiden Lane LLC solely to facilitate the purchase of Bear Stearns by JPMorgan by absorbing Bear Stearns’ most toxic assets—mortgage-backed securities, commercial mortgages, and derivatives that no one else would touch. It was necessary because JPMorgan refused to close the deal unless the Fed took the toxic assets off Bear’s books first.

In the end, the Fed contributed $29 billion, and JPMorgan added $1 billion, thereby creating a $30 billion fund to buy Bear Stearns’ most toxic securities. But the Fed has never released a detailed accounting of exactly what assets Maiden Lane purchased with its taxpayer-backed loans.

Among the exceedingly generous terms granted by the Fed, JPMorgan won the right to examine Bear Stearns’ entire portfolio and select which assets they would keep and which assets the Federal Reserve would buy. Among those assets was Bear Stearns’ 40 percent stake in Epstein’s Liquid Funding which, by this time, had $6.7 billion in liabilities from the same mortgage-backed securities and collateralized debt obligations that had precipitated the massive global financial crisis.

Then, on April 18, 2008, something remarkable happened. As first reported by Wall Street on Parade, Moody’s announced that “all outstanding rated liabilities” of Liquid Funding Ltd. had been “paid in full.”

But that was it. There was no explanation whatsoever regarding who paid the bills or how. So far as I can tell, there is no documentation in public records about how it was paid off. Bear Stearns no longer exists; JPMorgan Chase acquired what was left of it in May 2008. Whether Liquid Funding was consolidated on Bear’s balance sheet at that time is unclear. And when I asked Trish Wexler in corporate communications at JPMC about what happened to Epstein’s offshore venture, she replied via email, “I do not have anything to share with you on Liquid Funding.”

Multiple queries to the Federal Reserve also went unanswered and, at this writing, the Federal Reserve Bank of New York has not responded to a Freedom of Information Act Request regarding this matter.

As James Henry, an authority on the bailout, noted, “The Fed doesn’t really tell you who got what in this bailout.”

But in the end, even though the Federal Reserve never released detailed asset schedules for Maiden Lane LLC, the evidence overwhelmingly indicates that American taxpayers paid for Liquid Funding’s $6.7 billion in liabilities. The money had to come from somewhere, and, other than the Fed, no entity could have provided that kind of liquidity.

The Mysterious $6.7 Billion Payoff Of Liquid Funding's Liabilities

Liquid Funding’s liabilities had been paid off. It was, like Sherlock Holmes’ case of the dog who didn’t bark, a circumstantial case, but one that I believe is compelling.

The Federal Reserve has never released detailed asset schedules for Maiden Lane LLC, but the evidence overwhelmingly indicates that American taxpayers paid for Liquid Funding's $6.7 billion in liabilities. No other explanation is economically or legally plausible.

First, let’s remember that Bear Stearns owned 40 percent of Liquid Funding and managed the vehicle though its Dublin office. When JPMorgan acquired Bear Stearns with $30 billion of federal support, it acquired this stake. The remaining 60 percent ownership remains undocumented, including how much was owned by Epstein.

But at the time, JPMorgan served dual roles. It acted as Liquid Funding’s Security Trustee—an entity certifying that all debts had been paid—while simultaneously acquiring Bear Stearns with bailout funds and having the extraordinary power to select which Bear Stearns assets to include in the federal rescue.

So it is hard to believe that it was mere coincidence that, in the spring of 2008, at the exact moment when the Fed and JPMorgan were negotiating the $30 billion bailout, Moody’s announced that all Liquid Funding’s liabilities had been paid in full. After all, this was the only period during which that kind of money was available.

Moreover, the winding down of Liquid Funding occurred through a process called Members’ Voluntary Liquidation—a procedure that is available only when a company can pay all its debts in full. To be clear: that meant Liquid Funding’s creditors had to have been made whole. It was documentary proof that creditors were made whole.

We know that Bear Stearns couldn’t have paid for those liabilities because it was essentially bankrupt, and, at that moment, was surviving only on Federal Reserve emergency loans. We also know that JPMorgan wouldn’t rationally spend $6.7 billion to bail out an offshore subsidiary of Bear Stearns when it was buying all that was left of the collapsing company for just $1 billion.

Either way, whether the payoff came directly through Maiden Lane or indirectly through funds freed up by the bailout, the inescapable conclusion is that the Feds had rescued an offshore vehicle that had been chaired by Jeffrey Epstein just one year earlier. After all, if creditors had lost nearly $7 billion, don’t you think someone would have said something? There would have been massive lawsuits, news coverage, investigations. But there wasn’t. Nothing happened. It was extraordinary.

Meanwhile, the Great Recession got underway. The Dow fell 53 percent between October 2007 and March 2009. Nearly nine million jobs were lost. The business sector was devastated with more than 1.4 million bankruptcies filed in 2009. More than six million households lost their homes to foreclosure. Over two trillion dollars in wealth just disappeared. It took years to recover.

And in the end, the Feds had bailed out Epstein’s secret offshore company with $6.7 billion to cover liabilities created during the same years he was trafficking underage girls.

Note to readers: I attempted to reach Timothy Geithner, Jamie Dimon, FinCEN (the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network) and Federal Reserve officials for comment. None responded.

Craig Unger is the New York Times bestselling author of six books on the Republican Party’s assault on democracy, including House of Bush, House of Saud; House of Trump, House of Putin; and, most recently, Den of Spies,. Please consider subscribing to his Substack, from which this post is reprinted with permission.